How I scrummed my novel

Writing a novel is a lot like developing a software application. There are many moving parts that you have to devote great attention and concentration to as you conjure them into being, yet you also need to maintain a holistic view at all times. It can get overwhelming, but there are ways you can break it down. I was inspired by my Scrum studies at the time to use the method to finish my novel, even as a team of one.

First off, I cannot take credit for the idea of "scrumming a novel"; that goes to Karla Tipton, another writer and software professional. Karla says this:

'[Scrum Your Novel is] based on the concept of carrying on work at a steady-but-not-breakneck pace, undertaking work without a clear plan, striving towards attainable short-term goals, and then repeating the process towards another set of goals until the project is done. [...] What a perfect description of novel writing.'

Back in February, I took some time off work — a sprint of about 10 days — with the explicit aim of finally finishing off the first draft of my novel, which has been a seven-year work-in-progress. And I made it! This post is about how I integrated my new-found Scrum knowledge with my finishing process.

What's your Definition of Done?

The Sprint Goal, therefore, was to finish a complete novel draft ready for editing. But you won't get vary far unless you have a Definition of Done (DoD), as this is how all your progress will be measured. In a technical context, in order to be done, your increment must be in such a condition that it can theoretically be integrated into production.

It may be tempting to treat DoD as synonymous with the acceptance criteria, but the two are actually slightly different. (Here's a quick definition of how.) Most tickets for developing a new software feature will contain a user story. It will go something like this: "As a [type of user], I want to [be able to do something] so that [this thing will happen]".

This gives the developer a certain amount of leeway in how they go about implementing the ticket, as long as it meets the acceptance criteria. Whether or not the developer has actually implemented it in the best or most efficient way is immaterial for now. Note that we are emphasising done, not good. Done is better than perfect. Anything in between will be for the code reviewer to judge. For example, they may take a look at the code and point out a knock-on effect on another part of the application that the developer hadn't considered, and so the developer must then rectify it.

With a novel, I actually think this model is clearer. Your user story — or at least, an extended version of it — could be a paragraph-level synopsis of your novel. This synopsis doesn't necessarily need to be something that anyone else will ever set eyes on. However, to write the novel, you ought to have a reasonable sense of the protagonist's motivations and suchlike before you start. The acceptance criteria, then, might be in terms of how well these make sense with the plot.

Remember, we are focusing on attainable short-term goals here. Many authors will say that you are never really finished writing a novel; it just reaches a point where it is acceptable to you for publication.

Now let's recap Scrum's three pillars of empiricism and what they could mean within the context of writing a novel.

Transparency

Making sure everyone knows where you're at. For me, this involved some deep mindset changes. I had to deviate from regarding my novel as a top-secret project to hide from the world, to something I told people about as a legitimate thing I did in my spare time. I've always been one to hide my light under a bushel, and I decided I was simply fed up of that. When people at work asked if I was up to anything during my time off (this was back in dreary peak lockdown, mind you), I told them honestly. That was really scary! I also created a [public Instagram account](https://www.instagram.com/rosamundmather/) and made my intentions clear to my followers (or, well, anyone who lurks on my page). I also published an update when I was done.Inspection

Regularly taking stock of your work. This is core to carrying a complex project out to completion. Are you sticking to the specification or have you drifted off? If you have drifted off, can you justify it (with, say, a more believable backstory for a certain character)? If you are working in a team, inspection may come in the form of ceremonies like the Daily Standup or the Sprint Retrospective. When you're working on your own, however, that's going to require a lot more rigid accountability. Without honest inspection, you are not going to be able to adapt where necessary. Which brings us to...Adaptation

Implement changes as soon as possible to optimise the result. We might think of the novel as our "product" and its readers as "stakeholders". Some people might find that a gross analogy — and I don't blame them — but we're trying to get sh*t done here, okay? (I'd also argue that if your aim is to get published, it may even be beneficial to think in those terms.)For example, if you've written most of your novel and make the retroactive decision to kill a character off, you're going to need to adapt what you've already written so that person no longer shows up in places they shouldn't be. Maybe you've set yourself a certain day as your deadline, but then some kind of emergency comes up and you miss it. How are you going to meet your definition of done?

Working with increments

In this case, the only increments I'm addressing are the Product Backlog (PB) and Product Increment (PI). Sprint Backlog is kind of redundant here because I was only going to have one sprint, in which the aim was to entirely clear the PB.

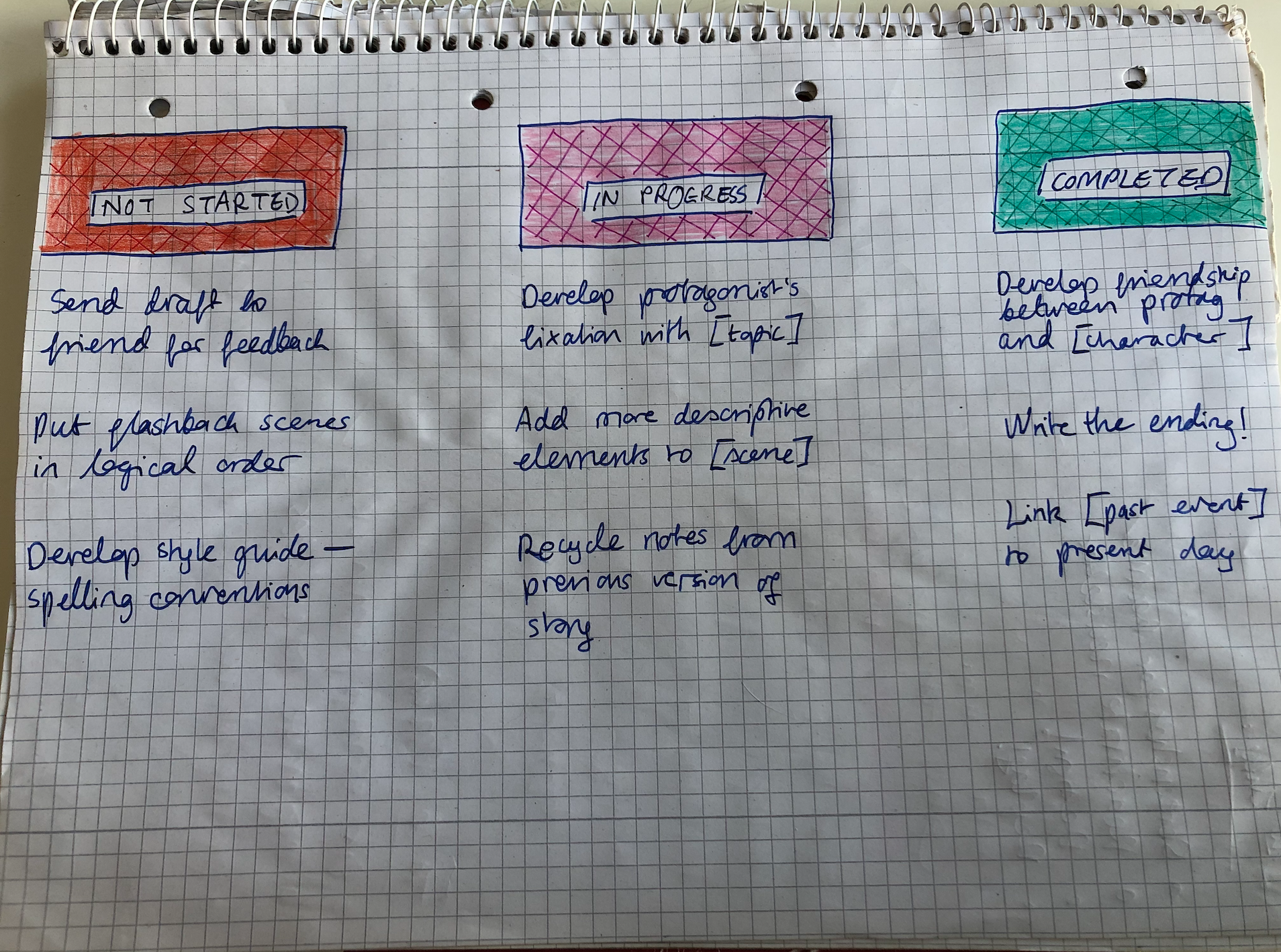

I've talked before about how awesome Notion is for planning your work and even your life. I had an entire new page for my novel-finishing endeavour, including a board representing the PB, so I had a clear overview of where I was at. Each PI represented an aspect of the novel I wanted to be complete. Here's a hand-drawn adaptation of what my Notion board looked like:

Once I moved a PI to the "Completed" column, that meant it was done. Each PI moved to that column brought me closer to achieving the Sprint Goal. I then had a completed novel draft! It's important to mention that the final PI was to skim over my work before handing it over to my first reader (my partner), which is really no different to getting a code review.

I've now got my first batch of feedback and so now I'm going to do it all again, implementing the suggestions and amendments where I agree they're appropriate. That will require another sprint, and I'll have to redefine the DoD, acceptance criteria, and so on.

Even though a sprint is a set amount of time, be sure to set realistic deadlines. Find a balance between flexibility and not being too lax. Unless you're under a contract, you are most likely in no real hurry to get the draft done. Look, I know how frustrating writing can be, and I know how it feels when you just want it to be out of the way! But remember, you're doing this for fun (...kind of). There's no boss looking over your shoulder; you're the boss. Adopting Scrum to get it done is just a way of making it a bit less overwhelming.